Heavy metals like arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury are increasingly found in the foods we eat. As we aim for healthier diets, we may unknowingly increase our exposure to these invisible threats. Ironically, the same whole foods praised for their health benefits may also harbor long-term toxins — making awareness and sourcing choices more critical than ever.

Heavy metals like arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury are increasingly found in the foods we eat, especially in grains, vegetables, seafood, and even chocolate.

These metals enter the food chain through contaminated soil, polluted water, and industrial runoff, then accumulate in crops and animals. Whole grains, while nutritionally superior to refined versions, often contain higher levels of metals because they retain the outer bran layer, where contaminants tend to concentrate.

Food is our source of nutrition, but it can also be a vector for toxic exposure. The presence of heavy metals in the human diet—many of them carcinogenic or neurotoxic—poses a growing concern for global food security and public health.

Among the most affected food types are grains, especially rice and wheat, and leafy vegetables, which can accumulate metals from contaminated soils, irrigation water, and industrial pollution.

Ironically, the very features that make whole grains nutritionally rich also predispose them to higher concentrations of toxic elements.

What are heavy metals?

Heavy metals are naturally occurring elements with high atomic weights and densities, such as arsenic, lead, cadmium, and mercury, that become toxic to the human body even at low levels.

Unlike nutrients, they serve no beneficial role and instead accumulate in tissues over time, often interfering with the nervous system, kidneys, or cardiovascular health. While some exist in trace amounts in soil or water, industrial pollution, mining, and agriculture have significantly increased their presence in the food chain, turning once-safe foods into potential sources of long-term exposure.

Arsenic: In the grains

Arsenic, particularly its inorganic form, is a well-documented carcinogen and endocrine disruptor. Rice is notably efficient at arsenic uptake because it is cultivated in flooded fields, which create anaerobic soil conditions that convert arsenic into more bioavailable forms.

This is especially pronounced in regions with high geogenic arsenic levels, such as Bangladesh, India, and parts of China.

Brown rice, by retaining the bran layer, also maintains significantly more arsenic than white rice. Since arsenic concentrates in the outer layers of the grain, polished rice typically contains 50–80% less arsenic.

Whole grains such as brown rice, black rice, wild rice, and whole wheat, while offering superior dietary fiber and micronutrients, present a tradeoff between nutrition and contamination.

Pro Tip: To reduce the amount of arsenic in rice, first clean it, then boil it in a large amount of water for about 3 minutes, then discard the water. Return the rice to the heat, add boiling water, and cook as usual.

NOTE: White basmati rice has consistently ranked among the lowest in inorganic arsenic, the most toxic form of arsenic found in rice.

Cadmium: In our bread, biscuits, potatoes, and chocolate

Cadmium is a naturally occurring element, but is significantly concentrated by anthropogenic activities such as phosphate fertilizer use, industrial emissions, and improper disposal of electronics and plastic waste.

Cadmium can travel long distances through the atmosphere and settle on crop fields. It accumulates efficiently in leafy greens (e.g., spinach, lettuce) and cereal grains, especially in the germ and bran of wheat and rice.

Wheat cultivated in areas with high soil cadmium, such as some parts of North America and northern Europe, can contain elevated levels, though these are generally regulated. Again, whole wheat flour tends to contain more cadmium than white flour because it retains the germ and outer layers, where cadmium tends to concentrate.

Foods with higher cadmium:

- potatoes and potato chips

- leafy vegetables

- wheat and cereal products

- chocolate

- Pastries

- seaweed and seafood

Prolonged exposure to cadmium can cause kidney damage, bone fragility, and mineral depletion.

Lead: The neurotoxic metal

Lead contamination in food results primarily from legacy pollution—such as old leaded gasoline residues and proximity to industrial sources. Paint, ceramics, batteries, cosmetics, and contaminated soils can also be sources of lead.

Root vegetables like carrots, sweet potatoes, and tubers such as cassava are particularly vulnerable, mainly when grown in contaminated soils. Leafy vegetables, rice, and other grains grown in urban or peri-urban agricultural zones often reflect the legacy of heavy metals from human activity. Spices also contain lead.

Lead affects the brain and nervous system, and children are particularly vulnerable because it can affect neurodevelopment and impair cognition. It can also lead to hypertension.

Mercury: Bioaccumulation

Unlike other metals, mercury, especially in the form of methylmercury, is present in aquatic food chains, particularly in predatory fish such as tuna, swordfish, and sharks.

Microorganisms in aquatic environments, such as sulfate-reducing bacteria, can biomethylate mercury to produce methylmercury, which is taken up by phytoplankton. Phytoplankton are then consumed by small fish, which in turn are eaten by big fish.

Methylmercury bioaccumulates and biomagnifies. Thus, large predatory fish are more likely to have high levels of mercury as a result of eating many smaller fish that have accumulated mercury through phytoplankton ingestion.

This logic also applies to humans: If you consume a lot of small fish like sardines and anchovies, you'll also accumulate mercury in your body, especially if you don't detoxify efficiently.

Mercury can also enter the terrestrial food chain through atmospheric deposition and local industrial activities. Wild mushrooms and certain grains grown near coal-burning power plants or mining operations may accumulate trace amounts of mercury.

🦪🦐 Shellfish: Small, Big Risks

Oysters and shrimp may seem like harmless delicacies, but both are known to accumulate high levels of pollutants. Because they feed by filtering or foraging near the seafloor, they absorb heavy metals like cadmium, arsenic, and lead, especially in contaminated waters.

Oysters are also prone to microplastics, algal biotoxins, and viruses like Vibrio — risks that aren’t removed by cooking. Shrimp, especially farmed varieties, may contain antibiotic residues, industrial chemicals, and pathogens if sourced from poorly regulated regions.

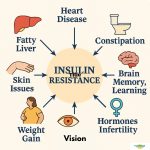

Heavy metal toxicity

Heavy metal toxicity occurs when metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, or cadmium accumulate in the body faster than they can be excreted, leading to cellular damage, inflammation, and organ stress. Unlike short-term exposure, this form of toxicity often develops silently over time, with symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, digestive issues, or developmental delays in children.

In more severe cases, heavy metal buildup can contribute to neurological disorders, kidney dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. Because many metals accumulate gradually through food, water, and air, toxicity may go unnoticed for years, making early awareness and prevention essential.

Conclusion

Heavy metals in food present a complex challenge at the intersection of nutrition, agriculture, and environmental health. While whole grains are widely recommended for their health benefits, they are also more susceptible to accumulating harmful metals, particularly arsenic and cadmium.

Future agricultural policies and consumer awareness campaigns must focus not only on what we eat, but also where and how our food is grown.

Comments

No Comments